During the Cold War in Latin America, the United States mastered a number of tactics in the art of political rhetoric in order to push interventionist policy with public support, tactics that it carried on using up until this very day in the modern War on Terror. The ability to frame interventionist policy in neighborly way was one of the great successes of the US administrations in their military interventions in both Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Two key tactics used by the United States in both Cold War Latin America and in the modern War are Terror are the classifying of ideologies as a foreign threat that needed to be fought, and the framing of allies as “Freedom fighters” and enemies as “Terrorists”.

Classifying as Foreign Threats

An Important tactic developed by the United States during the Cold War in Latin America was its ability to have Latin American Head’s of State subscribe to US Anti-Communism policy. The United States was able to do this by pushing forward the Declaration of Caracas in 1954, a statement that classified communism as “incompatible with the concept of American freedom.” This declaration was signed onto by all Latin American Nations except Guatemala. President Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala was a leftist leader who called for a rejection of US influence in the region. He adopted a policy of land reform that included the expropriation of 200,000 acres of land from the United Fruit Company and the redistribution of that land. Following Arbenz’s objection to the Declaration of Caracas and his “pink” policies, the United States supported a coup against him.

This same tactic can be shown to be used in the Modern War on Terror in Iraq, where post 9/11 President George W. Bush gave speeches in which he said “The enemy of America is not our many Muslim friends; it is not our many Arab friends. Our enemy is a radical network of terrorists, and every government that supports them.” In this statement, Bush sought to do the same thing as was done through the Declaration of Caracas, on board Middle Eastern nations to justify the US invasion of Iraq under the lure of a foreign threat.

“Freedom Fighter” or “Terrorists”

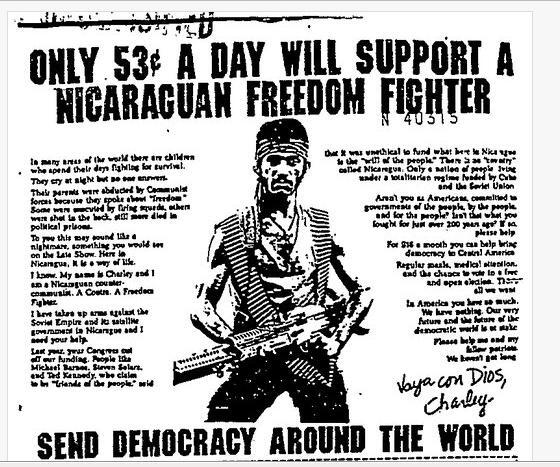

Another key tactic by the United States during the Cold war was the use of labeling allies as “Freedom Fighters” and enemies as “Terrorists.” This was especially useful at a time were “terrorist” was polling as more fearful then “communist.” In Nicaragua, Ronald Reagan forwarded this tactic by referring to the Nicaraguan Contra Rebels as “Freedom Fighter” fighting for “American Values”. At the same time the Office of Public Diplomacy in Central America and the Caribbean attempted to associate the Sandinista government with terrorism by accusing them of having connections with Libya, the PLO, and other US-designated terrorist groups.

Similar tactics were used against Iraq leading up to the US invasion. During Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the US worked hard to create a campaign similar to that of Nicaragua. It sought to characterize the Iraqi army as cruel and evil, and worked closely with the Committee for a Free Kuwait and a Republican PR firm to launch this campaign. Pictures were staged to show atrocities done by the Iraqi army, videos were created of Kuwaiti “freedom fighters”, T-shirts were distributed, “Free Kuwait day” was declared, and media groups pushed these elements all day long. An account by a 15 year old volunteer “Nayirah” was given at Capitol Hill, in which she described gruesome scenes of Iraqi forces tearing babies out of incubators and throwing them on the floor. While this account pushed Americans to sympathize with Kuwaiti Freedom fighters while despising Iraqi “terrorists”, it was completely fabricated. The campaign by President George Bush Sr. at the time to label Iraq as a terrorist regime would set the groundwork for President George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, capture of Saddam Hussein, and 9 year war.